"Community Review"

[Background]

Excerpts from Former Mayor, Keisha Lance Bottom’s 1st “State of the City Address”

With the establishment of the first-ever “Mayor’s Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion”, Atlanta’s then-Mayor, Keisha Lance Bottom, looked to “shine a light on forgotten communities and build a bridge towards greater inclusiveness across the entire city”. To accomplish this, the “One Atlanta” office, ultimately looked to

Implement city-wide improvements that could ensure more equitable access opportunities

Assess the effectiveness of previously implemented strategies across citywide departments and neighborhoods.

[Challenge]

While the overarching goal of “dismantling systemic inequities and barriers to opportunity” does inspire confidence amongst constituents, the evidence of this dynamic is nuanced and often invisible to a person’s everyday experience.

For the city to validate its capacity to become more “equitable”, it would need to identify datasets of “inequity” and translate them into outputs that felt actionable for public officials, observable by the general public, and comprehensible when these two groups held civic discussions around how to address them.

[Focus]

The goal of this project was to specifically contextualize the notion of “equity” as it related to the perception of supportive and/or celebrated infrastructure within any residential area.

[Approach]

While maintaining an interest in honoring the diversity of each Atlanta neighborhood, we endeavored to create an inclusive, participatory experience which allowed residents to create interactive, self-reported definitions of “equity” via geo-tagged artifacts that either exemplified their understanding of this term or contrasted it (thereby noting “inequity” they desired to be addressed).

By essentially crowd-sourcing this spatial data from local residents, city-officials could instantly conduct contextual inquiry, encourage real-time civic-participation, and aggregate geo-fenced datasets to understand how these stratified perceptions of “equity” could be addressed in more nuanced, community-specific approaches.

[Metrics]

For both the public officials (facilitators) and residents (users) we looked to test with, our main priority was confirming the following factors as it related to the usability of our concept:

-

Could both groups effectively use any digital and/or physical product for the purpose of identifying any physical location and providing qualitative context to the importance of this marked coordinate?

-

Do both groups perceive the experience of completing this key task as meaningful and enjoyable?

-

Could this inspire both groups to consistently use this project’s output as a means of civic participation / data analysis?

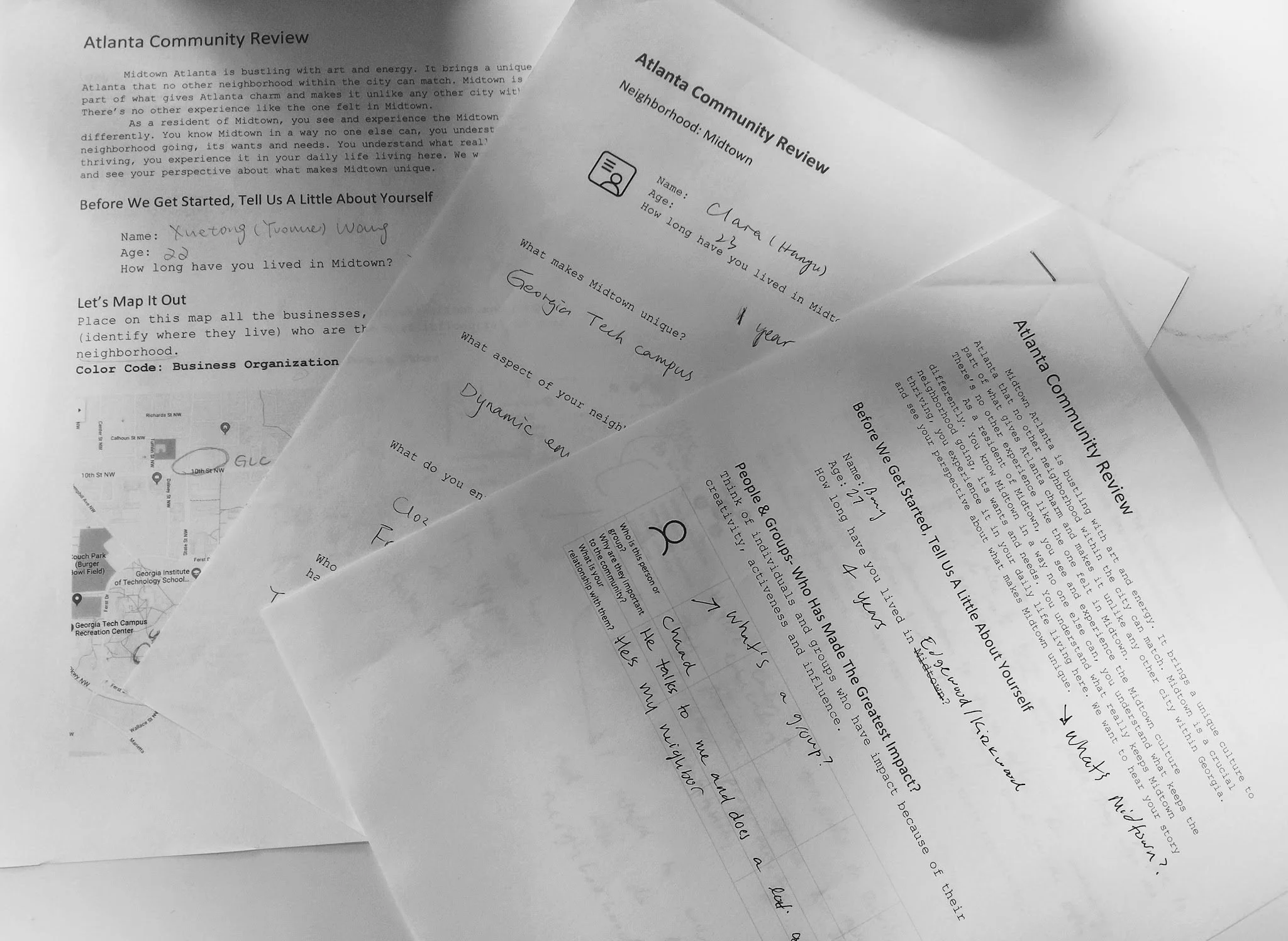

[Generative research]

To initiate our project strategy, we needed to answer initial questions like:

“How could Atlanta communities define contextual ‘equity’ or ‘inequity’ data so that it can be aggregated?”

“Where could this reported data be made accessible, visible, and quantifiable?”

“In what ways can we further engage the experience of resident reporting to help materialize the idea of “equity”?

-

Because the nature of this project desired to make “equity” visible, our first interest would be to elevate any pre-existing concepts that could be used as physical evidence for the presence (or lack) of equity.

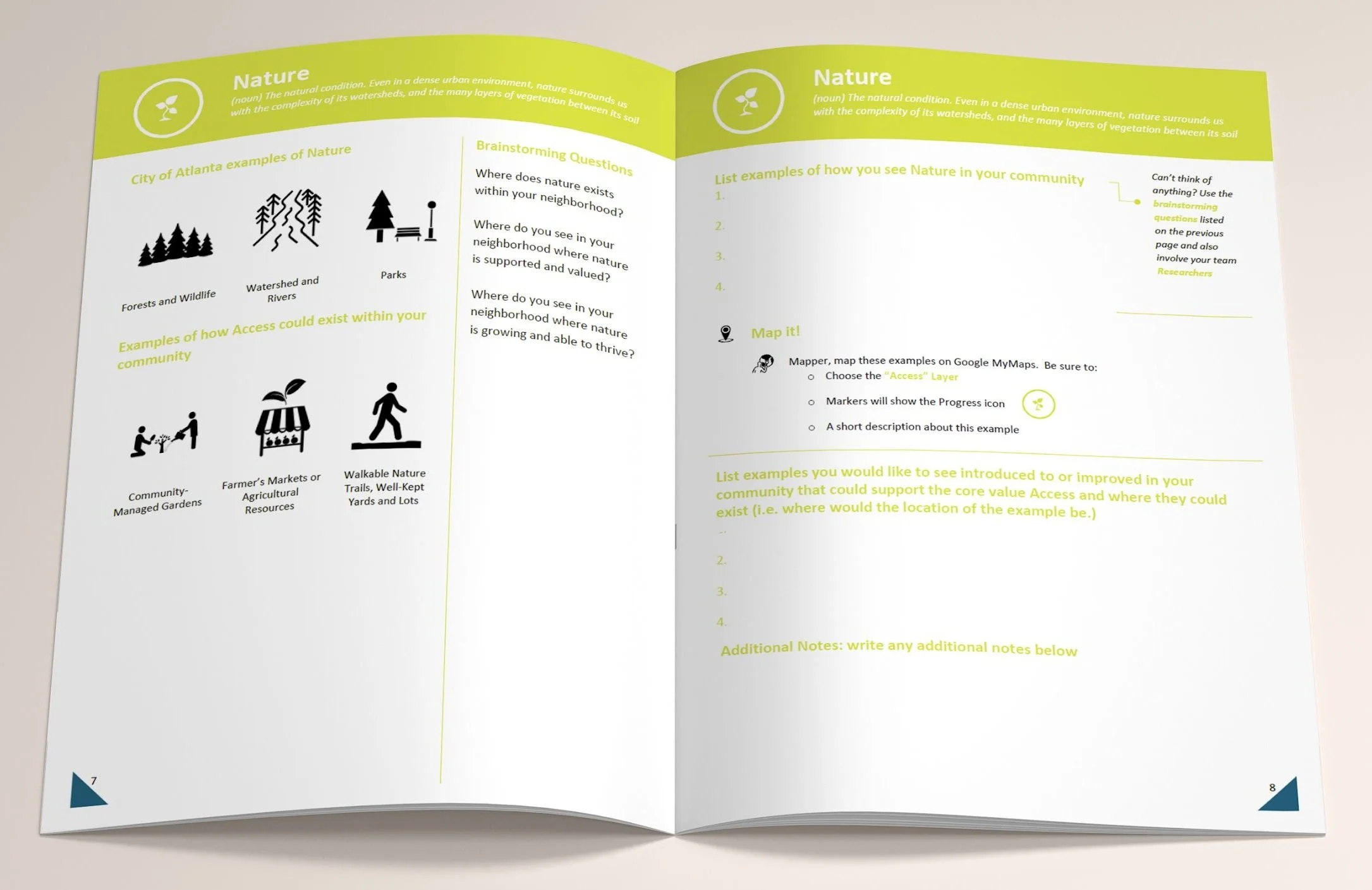

Through an extensive review of several forms of media, city ordinances, zoning codes, and archived documents we eventually settled on the framework provided by “Atlanta City Design” and its core values of “Progress”, “Ambition”, “Access”, and “Nature”. With each of these predefined values already integral to the design of physical infrastructure in Atlanta, we saw the opportunity to build an accessible and inclusive taxonomy around “equity” that (a) residents could organize the assets they identified (b) co-opted familiar ideals from a publication often referenced by city-government officials.

-

The main incentive of our product hinged on the ability for residents to provide geographical and spatial data. Because the experience of publishing a report was imagined to be as seamless as writing an online review of a product / service, the goal was to find a digital platform that could…

(a) simulate this same interaction

(b) possessed an interface that was user-friendly

(c) could be easily reviewed by any party that had access to a mobile-device. -

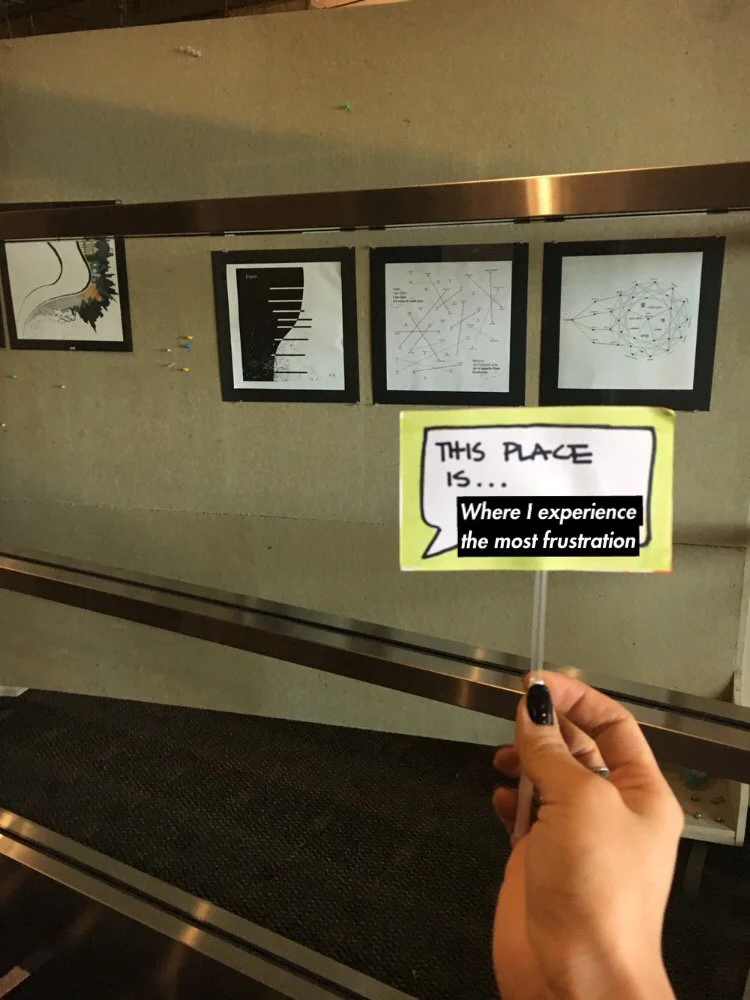

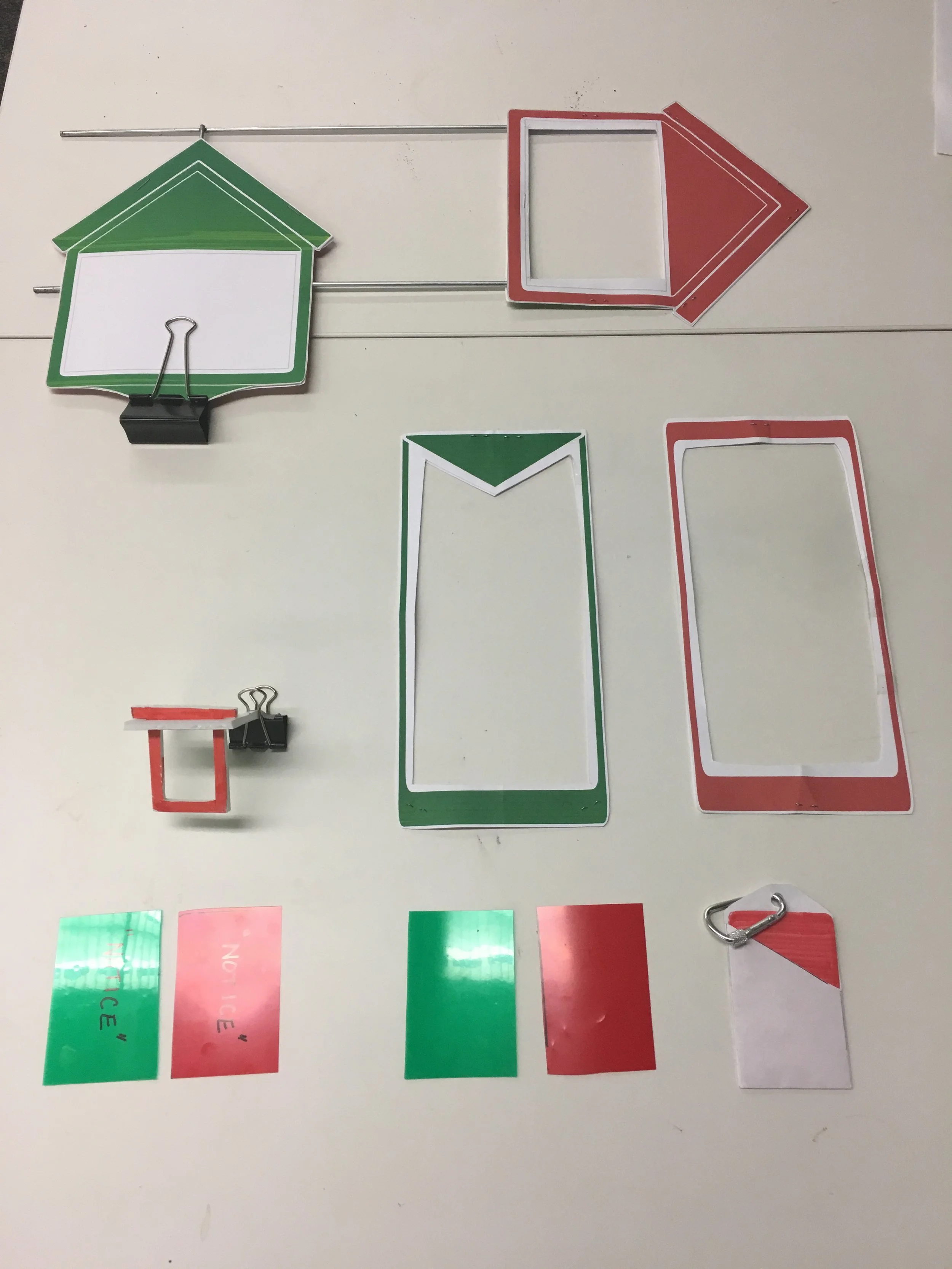

To complement the physical dimension of residents identifying places in their immediate surroundings they wanted to elevate for review, the initial intent was to provide a physical-item to complement the digital geo-tag they would be producing; inspiration was pulled from yard-signs, canvassing material, and other pre-existing signage used in residential areas.

Several concepts were sketched and rapidly prototyped to consider how providing a physical form might elevate the visibility of a resident-report and inspire additional response and/or collaboration. In addition, the opportunity for physical-digital interaction between these two features of our product were explored to consider their impact as both standalone and complementary items; after rounds of testing, this specific physical component was considered supplemental and focus was placed on generating a physical touchpoint that would be more critical to capturing more nuanced meta-data from resident reports.

-

Across our team, time was spent conducting participant observations in neighborhood meetings across the city to gain insight on what current artifacts were helping facilitate productive meetings; it was our interest to ultimately activate the ways that residents identify areas-of-interest in their neighborhood by matching the aesthetic and functionality of their current assets instead of disrupt it by trying to introducing completely foreign technology that require a certain level of tech-literacy.

[evaluative RESEARCH]

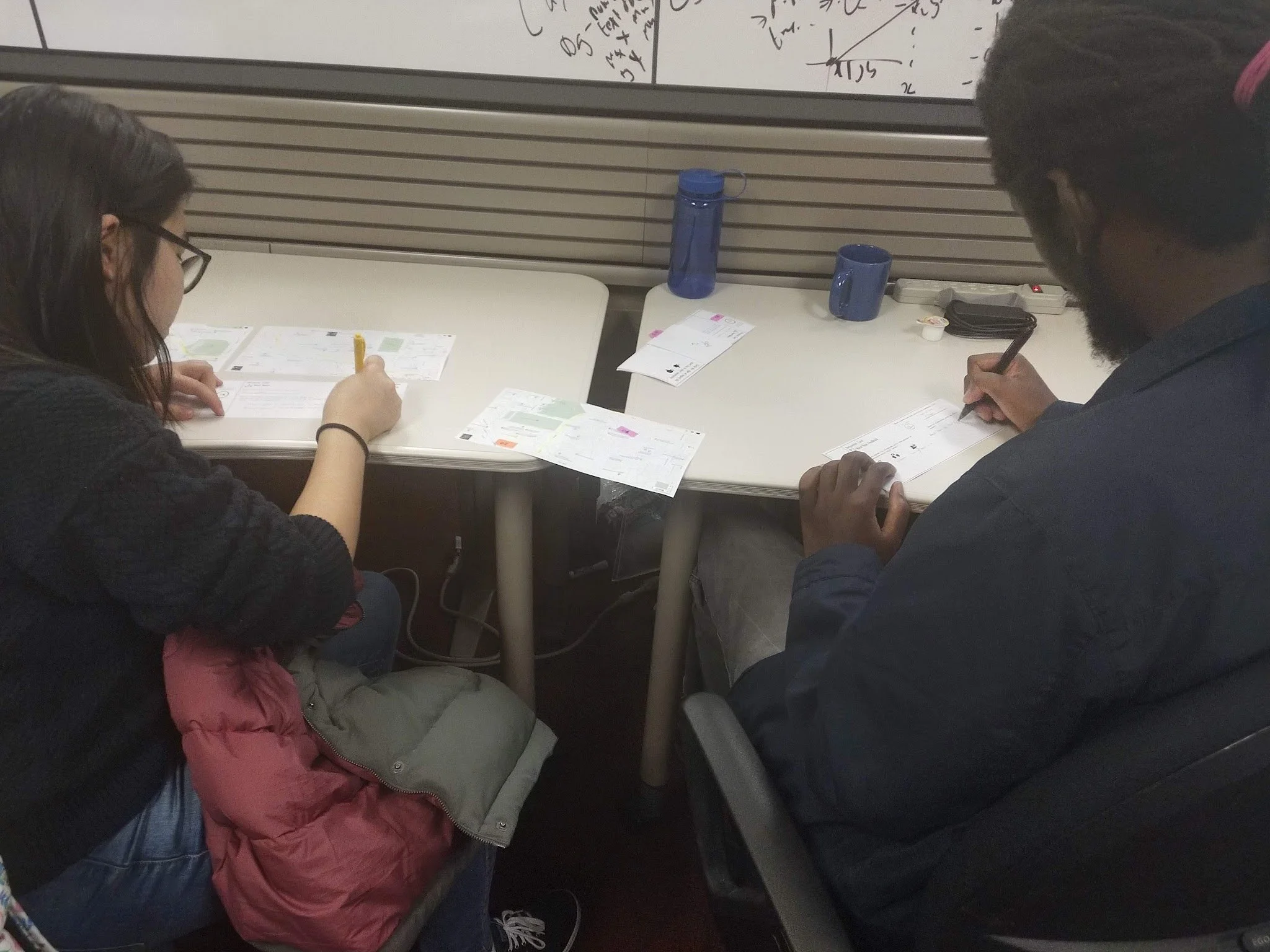

Because of the specific human-to-product and human-to-human interactions we wanted our service to help accommodate, we felt it was necessary to study the impact of our refined prototyped material in specific environments where we both residents (serving as participants) and city-officials (serving as facilitators) would be most likely to interact.

-

After conducting participant observations of two civic spaces, we were able to test with residents to gain early, qualitative feedback on our rough product-offerings and project metrics. Furthermore, we were given a final opportunity to test the full simulation of our toolkit and accompanying workshop with employees of the City of Atlanta’s Office of City Planning, who gave affirming qualitative feedback and guidance on how improvement to the product experience could impact our performance metrics.

[Key Insights]

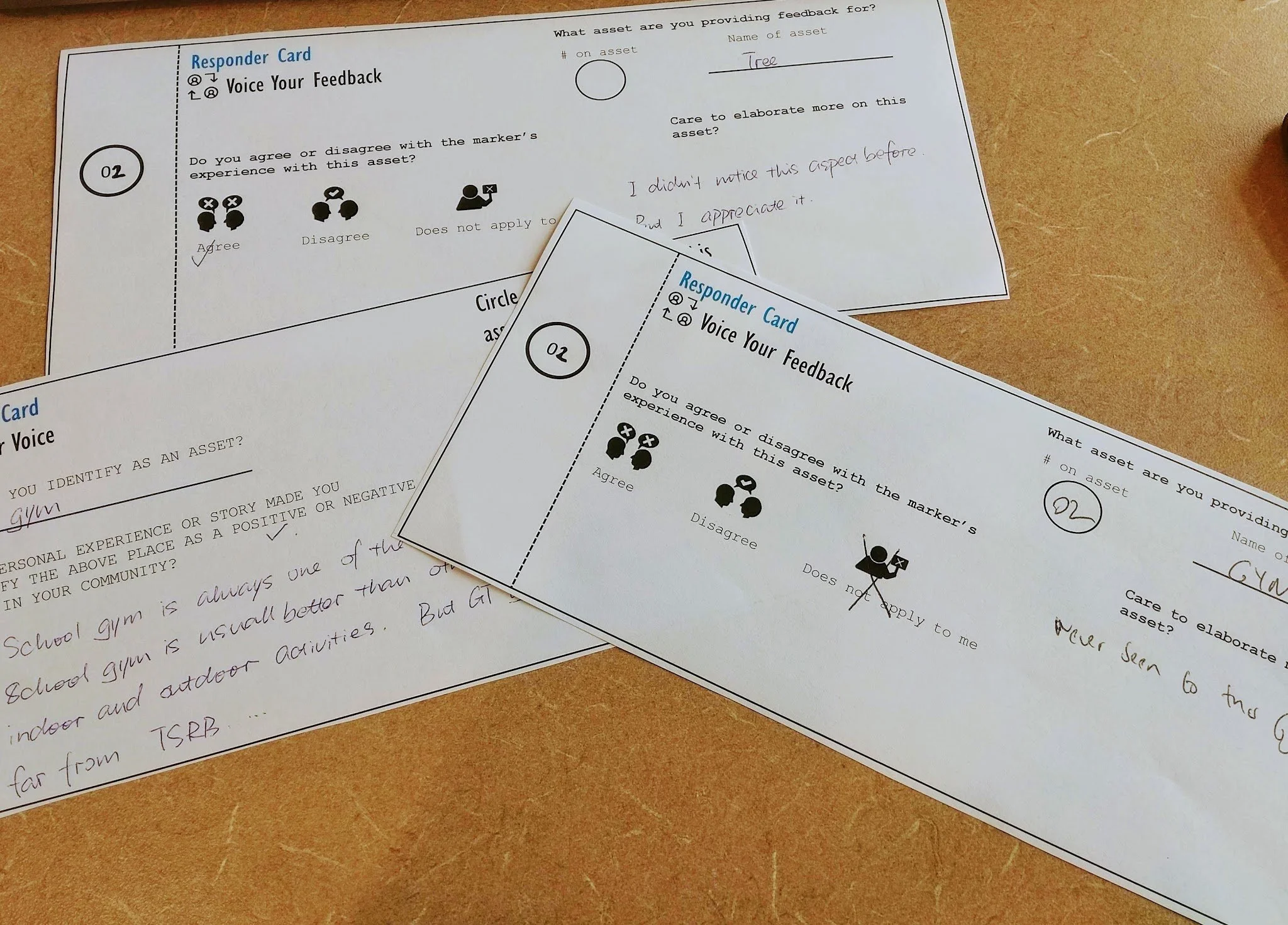

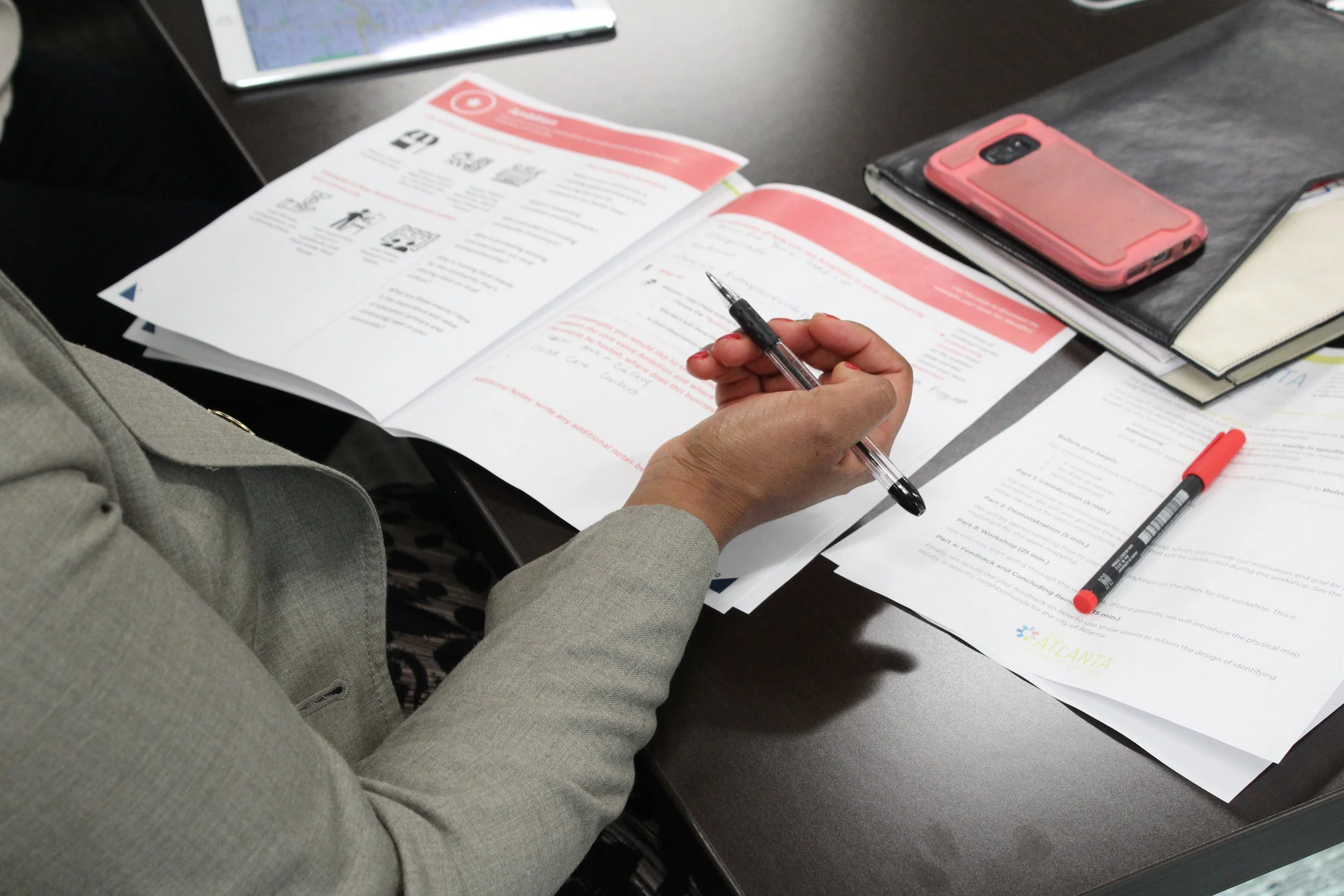

While the idea of being able to quickly and conveniently geo-tag / provide commentary on a location was initially imagined as an individual effort, our feedback when tested with both residents and city officials encouraged the opposite: people desired to do this work in a group setting where roles could be delegated and discussion could be held in real-time.

The most common arrangement of this group-preference was having (1) person who could identify a location while at-least (1) additional person provided annotation. Feedback reported that this allowed for each individual to have a sense of ownership over the activity without feeling overwhelmed.

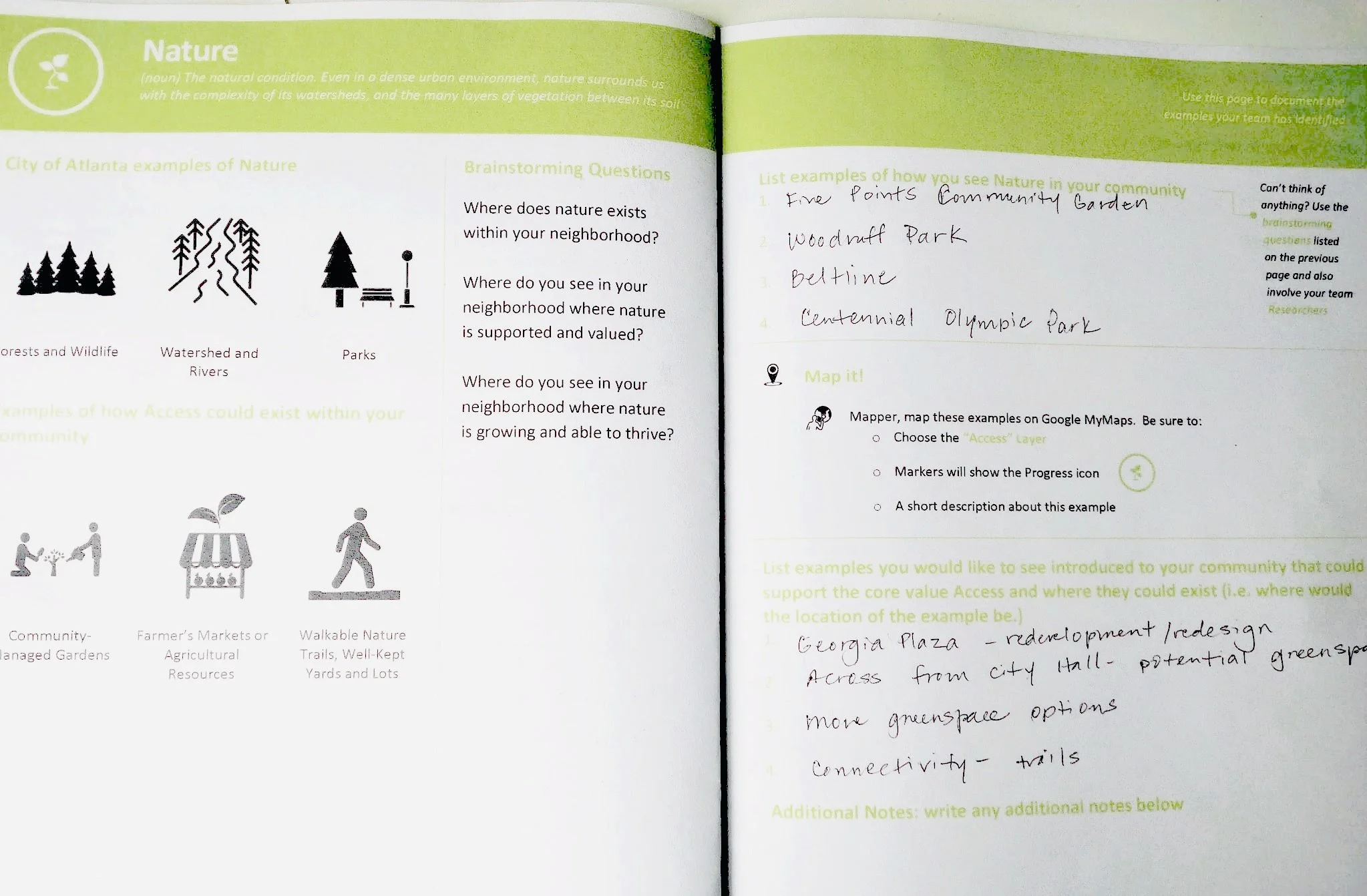

For many people, including government officials, this was the first time they had been engaged to assign a spatial identifier like this to places they commonly frequented and being able to brainstorm amongst their peers made this action easier to perform. Feedback requested that we remain mindful of this fact and provide facilitation of that brainstorm in a way that thoroughly introduced each of the core values in detail, starting with “Nature” as the first value and ending with something that was reported as harder to define by participants (like “Ambition” or “Progress”).

Most notably, when given the opportunity to use several methods of mapping which ranged from fully physical to completely digital, preference was shown for participants to use a physical workbook to capture their notes and a laptop to perform their geo-tagging.

[Proposed Concept]

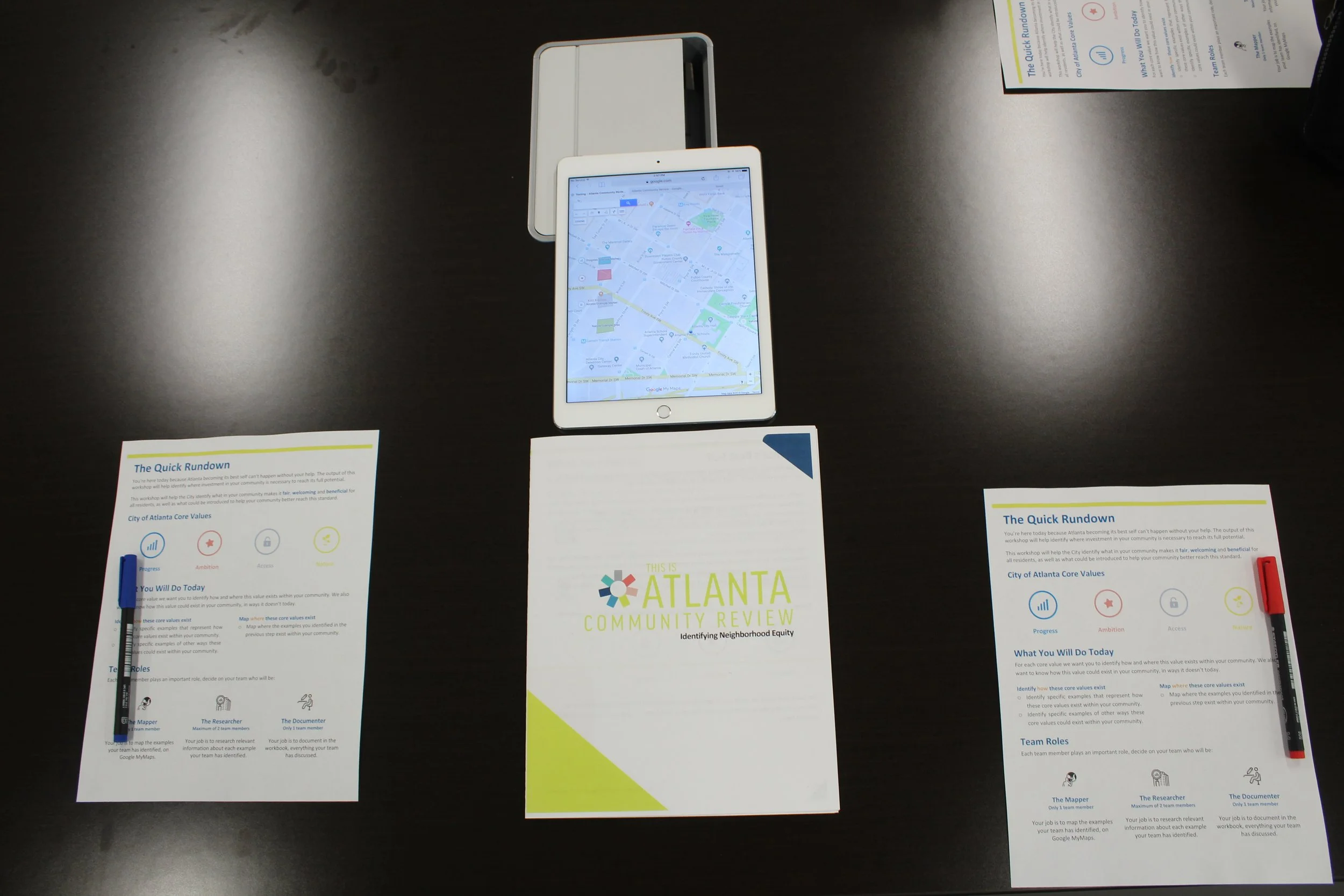

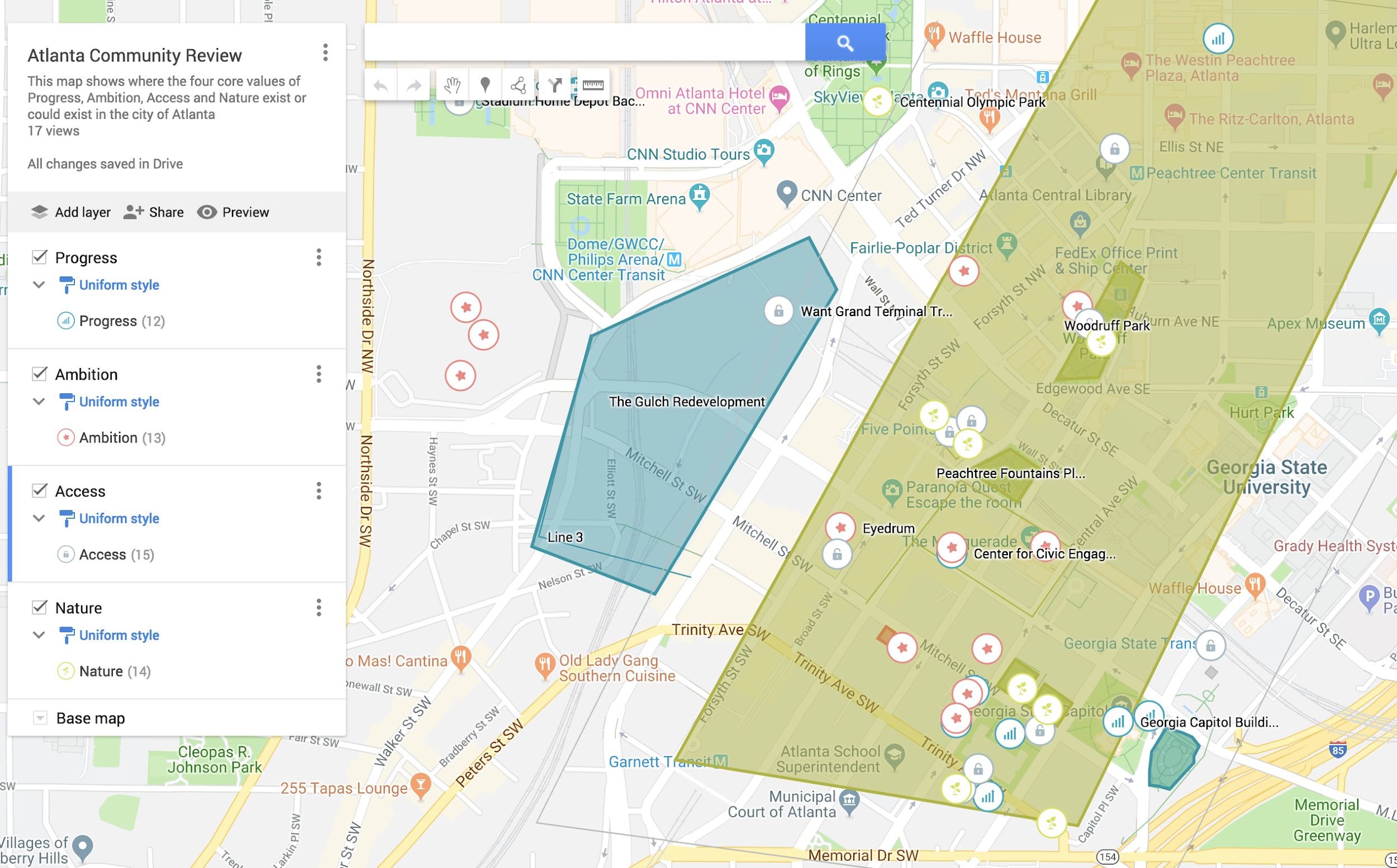

The core activity that drove this project’s output was “participatory asset-mapping” that leveraged a resident’s desire to identify places of interest around their local area; these “reviews” would be the main driver of our workshop / toolkit titled “Atlanta Community Review”.

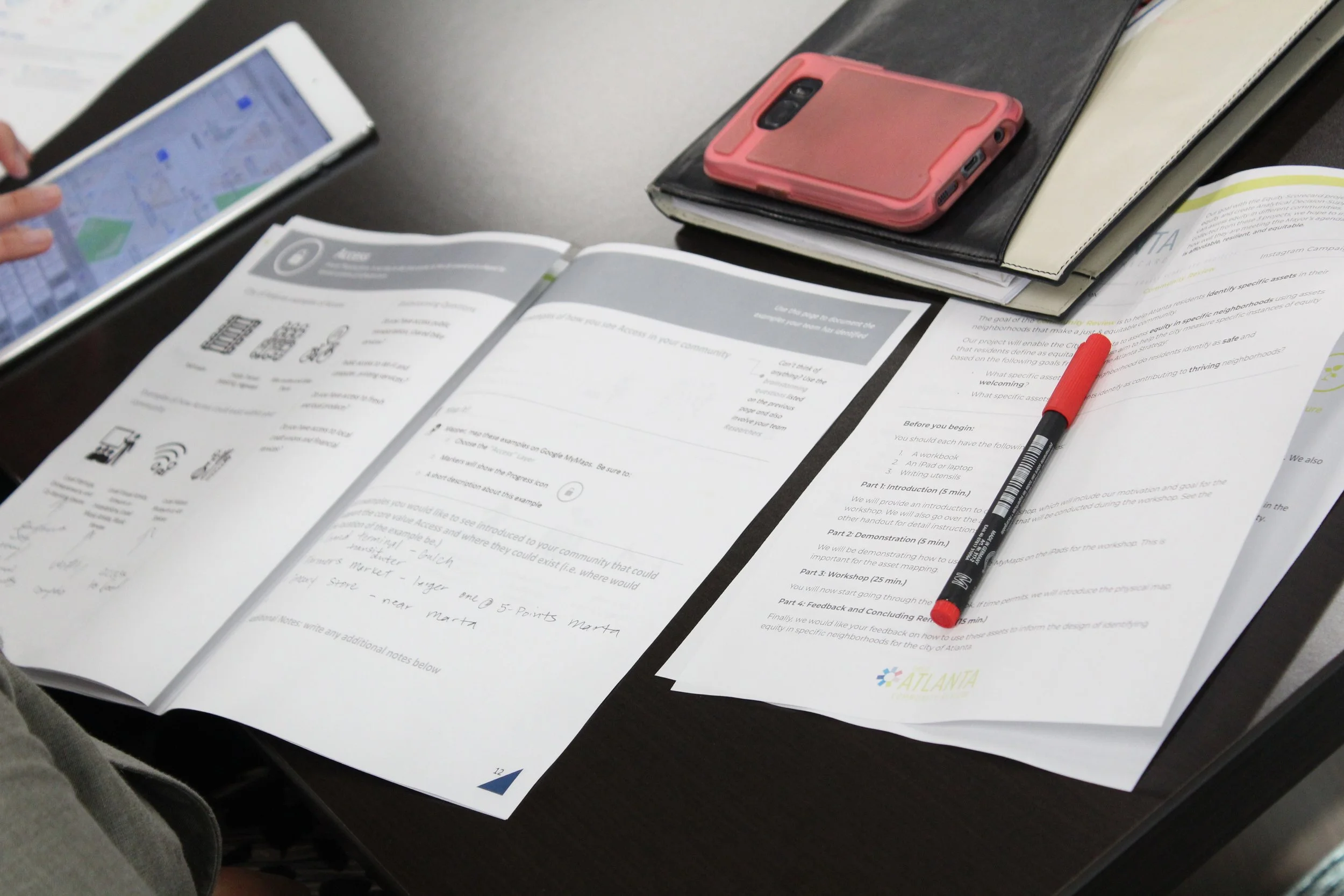

This workshop would provide participants with access to a specifically curated map of the city held through Google MyMaps. In conjunction with this web tool, participants would be given a physical workbook that provided step-by-step instructions to guide their geo-tagging and annotation of places they wanted to “review”.

Before conducting an audit of an area, individuals would first be taken through an introduction and explanation of an “Atlanta City Design” core value with contextual, visual examples. Upon being prompted with identifying their own examples, participants would be instructed to tag locations – using our curated Google Maps layer – that promoted the value they had just brainstormed with their peers. Finally, they would be asked to identify improvements they’d like to see which could help an area-of-interest further model details of that respective core-value.

Post-workshop processing would allow facilitators to confirm that digital data had been captured appropriately, perform data entry for any workbook information that might have been missed, and keep an accurate record of resident requests for improvements for later data-analysis-efforts.

[Post-Project REFLECTION]

-

In hindsight, this project was an ambitious endeavor to undertake in only 6-10 weeks. The very attempt to “operationalize equity” in a way that was concrete, observable, and accessible to the entire city already provided enough self-imposed constraints to keep our team preoccupied for much longer than the time we were actually allotted. Ultimately, the interest of making our content-strategy feel universal, tangible outputs feel accommodating to resident civic-environments (which often lack internet service or presence of digital devices), and overall product-system capable of real-time data visualization put a heavy burden on the “backstage” of this concept’s service model.

-

This project assumed that the City of Atlanta government would possess the budget and available internal / externally-sourced workforce necessary for the integration and sustained operation of our recommendations.

-

While our early iterations of place-making items did help inform our final outputs, the initial hyper-fixation with trying to produce a seamless interplay between highly-accessible digital and analog products was a tension that was never quite resolved. If released from the constraint of using technology and venues that accommodate a diverse range of tech-literacy, this project could likely exist as an augmented-reality service that could provide additional dimension to digital, community-facing platforms which are predicated on user-generated-data.