"Breathe Easy"

Layout Redesign for Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport

[Public & Facility Concern]

As the world’s busiest airport, Hartsfield Jackson International Airport regularly accommodates over 90 million passengers per year. With this large flow of people moving daily through the facility, the airport must be able to accommodate a diverse number of lifestyle practices. One such activity, which gained a large amount of negative stigma due to on-going awareness campaigns, was the smoking of tobacco products directly outside the airport’s terminal buildings.

The original location of smoking areas, which borrowed space from the waiting areas for arrival pick-up, raised concerns with both passengers and airport officials; for non-smokers their immediate proximity to smokers presented personal concerns about their exposure to second-smoke while facility managers raised concerns about the toxins from smokers being drawn inside the building due to negative pressure.

[Client Concern]

To make matters worse, the development plans for the airport’s new remodeling details coverings that look to elevate the appeal of the airport's facade while also providing weather-proof covering for idle passengers. With the current layout of smoking areas, this canopy provided additional concerns that airborne toxins would be trapped above airport customers and impact the maintenance schedule of these future installations. Ahead of their official campaign to prohibit smoking indoors, the Director of Customer Experience for Hartsfield requested consultation to understand how these concerns could be mitigated in a way that upheld the airports commitment to both health and passenger-accommodation.

[Focus]

Using an ICF-informed, design-for-public-health approach as the foundation for this consultancy project, our end-goal was to provide ADA-compliant amenities for the support of smokers while protecting the remaining non-smoking population and adjacent facilities from the airborne, tobacco by-products that were being produced outside the terminal.

A priority of this project was to create outputs that were intentional about addressing the concerns raised by non-smokers without disrupting the participation of outdoor smoking. In understanding the contextual factors and motivations held by smokers, we wanted to provide recommendations that wouldn’t perpetuate the growing social stigma assigned to tobacco-use as to preemptively avoid future scenarios where chemically-dependent individuals would purposefully rebel against future airport policies and disregard their accommodations in resistance to perceived public scrutiny.

[Descriptive research]

-

While the focal point of our project was to ultimately identify and address a human-centered design opportunity, it was important to first familiarize ourselves with technical factors that related to the current scenario. This lead to a review of studies that addressed the science behind human-generated air-plumes, the relationship between secondhand smoke and distance, and natural (i.e. outdoor weather like strong winds) or mechanical situations (i.e. negative pressure via indoor air conditioning) where air-flow could easily influence the way residual tobacco particulates could be spread to surrounding outdoor areas.

-

To validate our client’s concerns and confirm the relevance of our background research, we performed both guided and unguided tours of the outside terminal spaces. These initially started as unobtrusive so that we could familiarize ourselves with the diverse contexts upon which both smokers and non-smokers found themselves in proximity to one another. These observations were then used to construct a concise interview guide that allowed our team to quickly collect insight from both idle passengers and airport employees. This short series of interview questions looked to understand the transient nature of the people we observed to identify any nuance in the motivations, opinions, or beliefs that informed the locations that individuals chose with relation to designated / non-designated smoking areas. These qualitative interviews revealed that smokers held an acute awareness of what it required for them to indulge in this habit; despite feeling impeded by clear instruction, alienated by the lack of dedicated outdoor amenities, and even disrupted by disgruntled non-smokers (who were ironically standing in designated smoking areas), they were not deterred from taking a smoke-break while traveling or on-shift.

[GENERATIVE RESEARCH]

-

In compiling our interviews, it became clear that both smokers and non-smokers felt as if they belonged to a vulnerable population that was being impacted by the other’s negligence. However, this perception contrasted with the reality that both were hyper-sensitive to the presence of each other; in fact, the only explicitly observable behavior that initially separated our understanding of “non-smoker” and a “smoker” was the commitment to a single, brief activity. In wanting to have a deeper understanding of what that activity fully entailed, we focused our ethnography to compiling several studies of the “smoker community” across multiple days at varying travel times. Our interest was to not only understand the location, duration, frequency, and complimenting activities that comprised a “smoke-break” but to build a premise around how their current behaviors could be the result of an unmet need. Notably, this data revealed that these breaks lasted, on average, only 9 minutes where a slim majority actually took place in designated areas; during this time individuals largely preferred to stand while almost exclusively ashing on the ground (even in proximity to an ash-tray or trash-can).

-

To further synthesize our quantitative and qualitative data-collection, we worked to elevate the key components of our prior studies and contextualize them within a more comprehensive narrative of individuals experiences at the airport: from their arrival to the facility, to navigating their way to an outside area, to placing themselves in proximity to tobacco-use, and then their departure away from this space. This visual framework allowed for us to see important commonalities in individual experiences and identify the environmental factors that were contributing to pain points in the airport-customer-experience of the outside space.

[Key Insights]

In review of our research, it became clear that the current conditions were not a result of oversight by smokers who held disregard for public health. In fact, our research presented the novel insight that smokers were highly cautious of being exposed to the second-hand smoke generated from other smokers. With this concern in mind, they preferred to distance themselves from the larger public masses that gathered around nearby benches and trash-cans (which provided an ash-tray), and operate in solitude while using a cigarette.

This discovery, in conjunction with the analysis of the current amenities provided along the exterior of the terminal buildings, made it clear that the interactions taking place were the result of poor way-finding, information design, and place-making. The area for designated smoking areas was identical to its non-designated counterpart with respect to spacing, signage, and provision of amenities. This lack of distinction left individuals – who are transient and thereby concerned with punctuality and “time cost” – to either navigate unaware of where tobacco-use was prohibited or making a conscious effort to take m

[Proposed Concept]

-

By re-imagining the current messaging around tobacco-use as a shared interest in clean air-quality, the proposed campaign of “Breathe Easy” provided a unifying agenda of mindfulness for the environment and presented the opportunity for individuals to seek idle relaxation whether they navigated to a smoking or non-smoking area. This brand language focused on decreasing the specific stigma perpetuated by “non-smoker vs. smoker” by framing the entire outdoor terminal space as an area for health, wellness, and sustainability; this intentional shift away from a “human-to-human” or “human-to-policy” interaction to a “human-to-environment” exploration looked to guide people away from subconsciously assigning judgment, and thereby, stigma. To further enforce this shift in public-perception, the campaign assumed a color scheme that re-enforced the soft, “green”, and environment-friendly tone instead of the strong, authoritative warnings that currently existed. Ultimately the goal was to re-contextualize the shared space outside the terminal as a place to accommodate everyone’s preference for breathing and not the potential toxins smokers were breathing out.

-

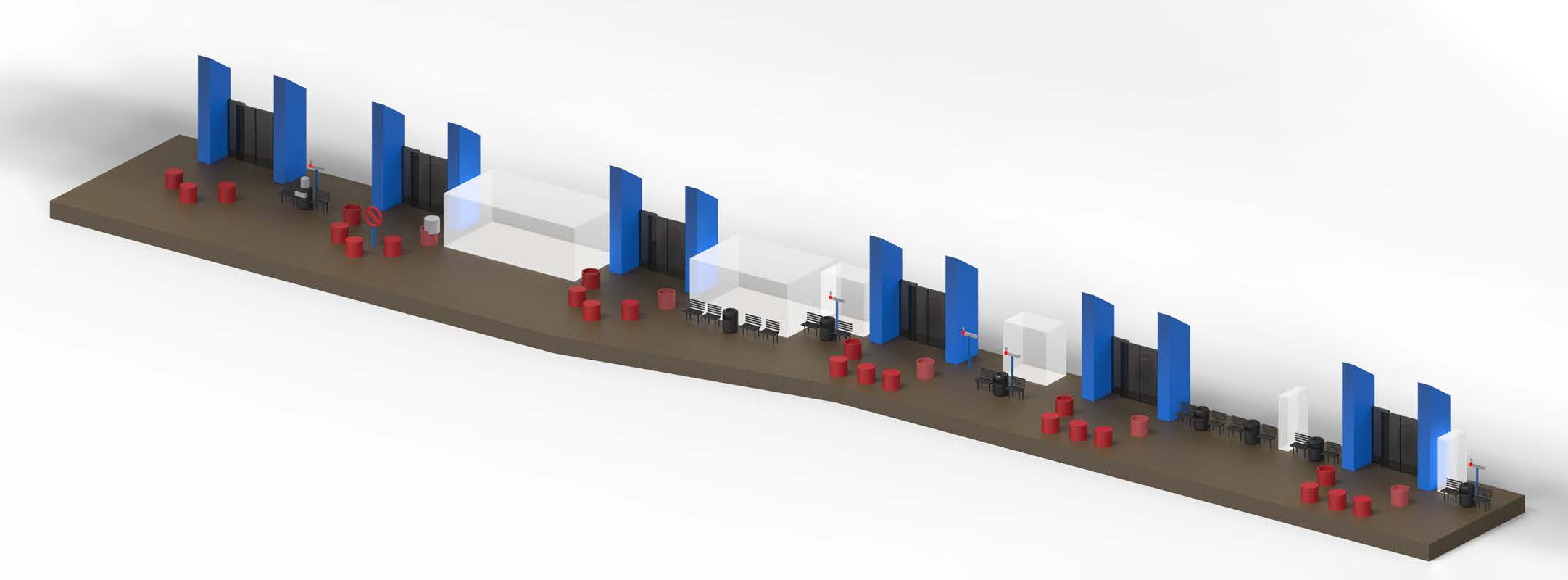

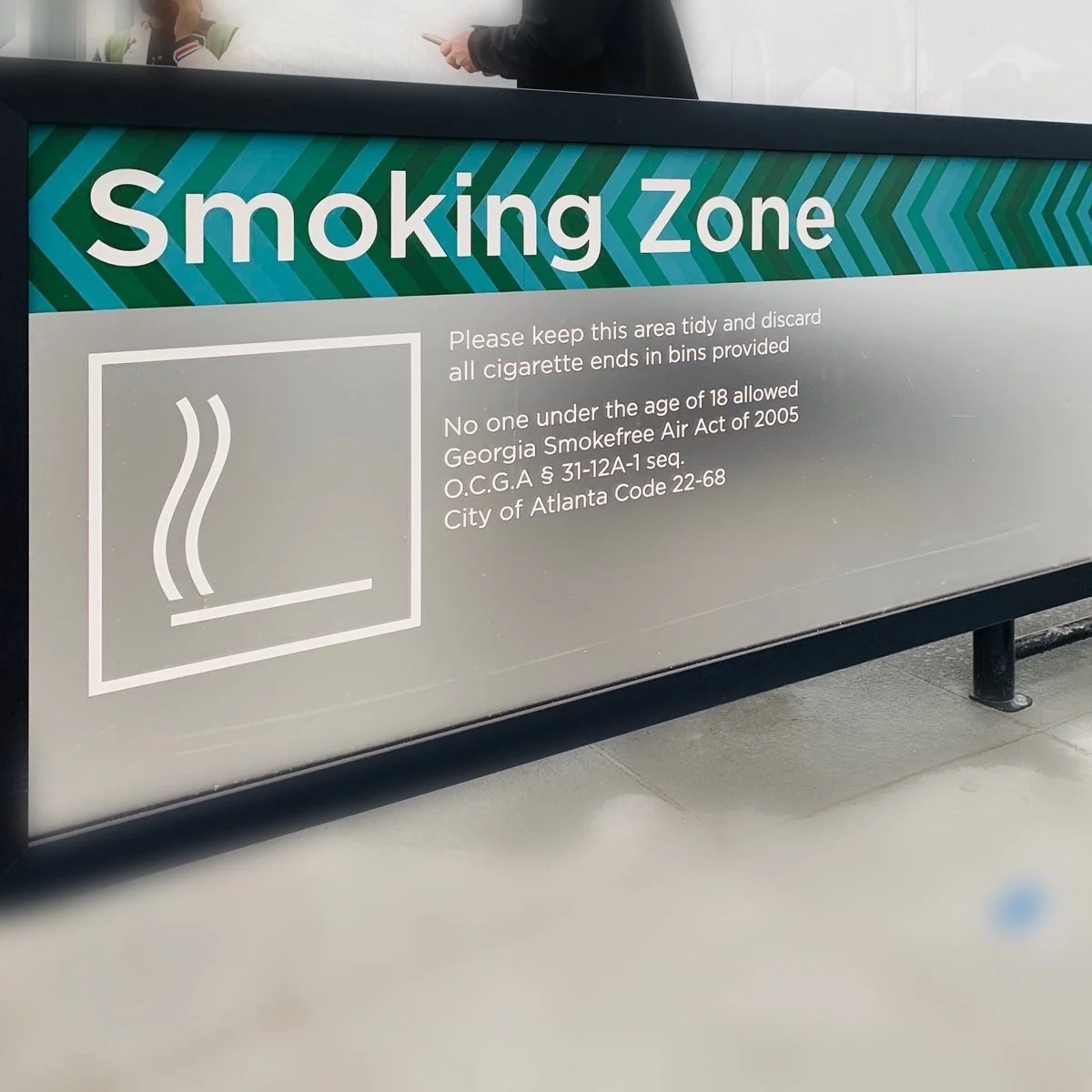

Early literature reviews directly informed the new proposed layout of the smoking sections; these diagrams provided a research-informed, recommended distance to help mitigate exposure to secondhand-smoke or air-plumes being pulled into the interior of the building. To account for this, the intermittently-placed smoking areas were consolidated into two larger smoking areas, placed at both ends of the terminal sidewalk. This shift allowed us to reduce confusion around the unclear boundary and identical signage that the previous locations instigated. A way-finding system, by way of new unique signage which further supported our social campaign, was recommended to replace the old system. With its installation, individuals would be guided to the closest smoking area based on where they exited the building. In wanting to convey direction but hold a softer tone, the construction of this sign looked to modernize the old sign while adopting the more rounded, organic forms proposed through our “Breathe Easy” design language: the background provides clarity to tobacco-use in a vibrant, green splash of color while elevating the foreground’s instructions for smokers to keep navigating towards their goal.

-

Upon arrival at a smoking section, individuals would be greeted with the same color-blocking used in the signage, now applied to the wall of the terminal building. This design recommendation looked to provide an explicit visual reinforcement of what two areas outside the two terminal building were (and implicitly weren’t) specifically provided to accommodate tobacco-use. In addition, the color-choice of this 2D element was done to introduce the “green space” culture that had been communicated through previous design elements while giving context to our new smoking amenity: the planter ash-tray. Taking inspiration from the flower-pot bollards already placed outside the terminal, these ash-trays would serve as an extension of the upcoming redesign of the airport’s interior (which would be covered in newly installed foliage) while providing smokers with an amenity that matched their observed behavior. Each planter would be placed so that smokers could stand or sit within reach of the ash-receptacle yet distanced away from their peers to account for their exposure concerns. With mindfulness of the additional horticultural upkeep these planters would require, recommendations were given for specific plants-choices that provided an elevated, “greenhouse” aesthetic to the space without constant maintenance; these plant-choices were also selected as a passive strategy to reduce the presence of airborne toxins due to their natural tendency to provide air filtration (implied by the NASA Clean Air Study).

[Outcome & INTEGRATION]

To date, the evidence of this nine-week design project is visible in the built-environment around the North and South domestic-travel terminal buildings of the Hartsfield Jackson International Airport. While not adopted “as is”, many elements presented in our design recommendation to the facilities’ design-team made it to the new iteration of the building’s exterior which include the new location of smoking areas, the complementary way-finding concept, and behavior-specific amenities for smokers.